HVO (“Renewable Diesel”) from plant or animal-based residual and waste materials is considered, alongside e-fuels, to be the most attractive fuel option for combustion engines in cars and trucks. We take the results from two new reports and show: the growth opportunities remain limited; the climate savings are greatly exaggerated; and fraudulent, large-scale imports of UCO and animal fats cannot be contained with the current EU certification system.

1. What is HVO?

HVO is the abbreviation for “Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil”. HVO (US term: “Renewable Diesel”) is vegetable oil that is purified of sulfur, oxygen and nitrogen in a rather complex process and converted into a saturated hydrocarbon, a so-called paraffinic hydrocarbon, by hydrogenation (catalytic incorporation of additional hydrogen).

HVO is therefore very similar to fossil diesel fuel and can be used as a so-called “drop-in” fuel in pure form or in any desired blending. This applies to diesel engines in cars or trucks as well as to more robust ship engines or, after slight adjustments, also in jet engines (HEFA fuels) .

HVO should not be confused with the much better known biodiesel (FAME), which is produced by the transesterification of vegetable oils and can only be added to modern diesel engines in limited proportions.

2. What makes HVO an interesting fuel? Three feedstocks

When HVO is produced from normal vegetable oils (rapeseed oil, soybean oil, palm oil, etc.), it is legally considered a conventional biofuel.

HVO only becomes economically attractive if the raw material (feedstock) used is not fresh vegetable oil (“virgin oil”), but so-called waste or residual oils of fats. These can be counted multiple times towards the GHG quota in many countries, making them far more attractive from the perspective of fuel suppliers.

These waste and residual materials almost exclusively belong to three groups of feedstocks:

1) Used cooking oils (UCO) from restaurants, commercial kitchens, the food industry or private households.

2) Animal fats that cannot be used as food, i.e. slaughterhouse waste in the broader sense (tallum). They are not mentioned so often in the advertisements for HVO, but they represent a rapidly growing feedstock share. Almost half of the animal fat feedstocks in Europe are already used for biodiesel. Stratas Advisors expects that by 2030 they will even be the second most important feedstock for HVO after UCO. Animal fats are divided into three categories, depending on the degree of health hazard (Cat.1-3, with Cat.1 being the lowest quality).

3) Residues from palm oil production, in particular palm oil mill effluent (POME). Palm oil itself is no longer allowed to be used for biofuels in the EU since 2023.

These three feedstock types are considered climate-neutral because their “climate backpack” is already assigned to their primary use or main product, e.g. when used as frying fat in a restaurant. Only the emissions generated by the refinery and resulting from the procurement and transport are counted. In my opinion, however, this is a rather arbitrary approach. Since it is ultimately a value chain, a portion of the climate emissions could be assigned to each individual value-added stage.

3. The UCO fraud wave

Since fuels made from waste and residual materials are legally privileged in the EU because of their better climate balance, their price is significantly higher than that of conventional vegetable oils. It sounds paradoxical: Used cooking oil has a higher market price than fresh vegetable oil. The same holds for POME vs. palm oil.

It is therefore lucrative for criminal traders and exporters to mislabel their products on a large scale. It was not long before a wave of UCO/POME fraud hit Europe. In 2024, the UCO market share rose to over a third of biofuel consumption.

The beneficiaries are, on the one hand, Chinese middlemen who, according to media reports, have been engaged in large-scale relabeling of fresh palm oil from Indonesia and Malaysia in China to waste (POME).

In particular, however, the alleged UCO quantities reached an enormous scale, causing prices in the entire EU biofuel market and greenhouse gas quota prices in Germany and other countries to collapse.

The big oil companies in Europe also benefit from this. They can meet their alternative fuel obligations at an unexpectedly low cost. Their zeal in uncovering the fraud was therefore limited.

Apparently, a similar situation occurred with animal fats. Offers in the highest category 3 were downgraded to categories 1 and 2 in order to obtain higher prices, according to various reports. The consequences for the climate could be very negative, since the lack of animal fats in their original markets would then mainly be replaced by palm oil.

With some delay, European, American and German authorities are now taking action against the countless fraud cases. It remains to be seen how successful this will be.

4. Certification does not work

Actually, these shenanigans should not even exist. The so-called “Voluntary Schemes” in the EU have been designed to reliably document the path of biofuels. For the imports of Asian UCO biofuels, the ISCC (International Sustainability & Carbon Certification) is particularly active. It currently certifies over 400 of these supply chains.

But the system has major gaps. The actual audits are not carried out by the ISCC, but by third parties, the “Certification Bodies” (CB). These are commissioned by the UCO suppliers, which is not ideal in itself, since the CBs have to compete for orders.

Even more serious, however, is the fact that only a small part of the audits actually take place on site or in the laboratory. Used cooking oil and virgin oil are chemically very similar and can only be distinguished with some effort.

Therefore, CB and ISCC mostly rely on plausibility checks of written documents along the supply chain. For example, restaurants and other small or medium-sized consumers that sell used cooking oil are usually never checked at all. An audit is only required for monthly quantities over 5 tons of UCO.

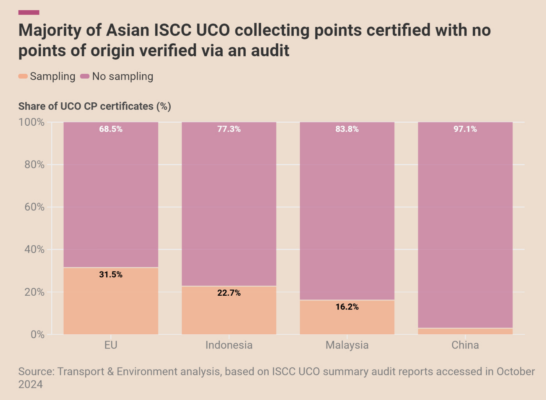

According to T&E’s analysis of ISCC certificates, only 9 percent of Asian UCO suppliers are audited. For the remaining 91%, a phone call or email is enough.

Source: Cian Delaney (T&E) 2024 (see source list below)

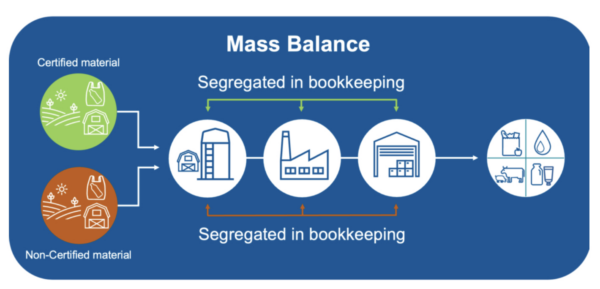

But that is only the first problem. The production and collection facilities for biofuels are also vulnerable. Verification is further complicated here by the so-called “mass balance” approach. Similar to the green electricity sector, certified UCO and non-certified virgin oils such as palm oil may be physically mixed and processed together along the supply chain.

Customers therefore receive „certified UCO„, which often only fulfills the requirements in terms of accounting, as it is allegedly fed into the supply chain in the specified quantity. It is obvious that this approach is prone to manipulation.

Source: Cian Delaney (T&E) 2024 (see source list below)

Despite the authorities‘ efforts, it can therefore be assumed that large quantities of incorrectly declared UCO continue to enter the European market.

5. Growth limits

The growth prospects for HVO in road transport, especially if it is to be produced from feedstocks such as UCO, are limited.

- Since Europe can only provide relatively small quantities of feedstock, more than 80 percent of UCO is already imported, especially from or via China, as well as from Indonesia and Malaysia.

- However, these exporting countries have rapidly growing domestic demand for both road and air transportation. The abolition of export subsidies for biofuels in China, which are often incorrectly declared, since the beginning of December 2024, is therefore probably only partly due to pressure from the EU. The introduction of sustainable aviation fuels and the increased use of biofuels in road and shipping in China itself are also behind this. The same applies to the major palm oil producers Indonesia and Malaysia, which are also introducing sustainable fuels.

- There are also limits on the European capacity processing of feedstocks into fuels. In 2024, there was only 5 million tons of HVO refining capacity per year in the EU. This corresponds to about 2 percent of the EU-wide demand for diesel. Shell has even stopped a major new construction project for an HVO refinery in Rotterdam.

- In addition, road transport is facing growing competition from air and sea transport. This applies to the FuelEU Maritime Regulation as well as to the new ReFuel EU Aviation Regulation from 2025. It stipulates a 2 percent share of Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF) in air traffic. For technical reasons, only HVO (HEFA = Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids) can be used for this purpose, and they will have to share the scarce production capacities with HVO for road fuels.

As a result, demand pressure is likely to increase not only for UCO but also for animal fats. By 2030, the use of these animal fats, known as “waste feedstocks”, in EU aviation could even overtake UCO. Neste, Europe’s leading HVO producer, already uses large quantities of them in its biorefineries in Finland and the Netherlands.

6. HVO100 in Germany

HVO was already approved in Germany before 2024, but was only used to blend fossil diesel in a proportion of about 2%. Since May 2024, HVO has now also been allowed to be offered in Germany in pure form as “HVO100” or “paraffinic diesel”. This has been the case in some other European countries for some time.

However, the change will only result in a redistribution of HVO volumes in Germany and the EU, as Agora Verkehrswende notes. Nevertheless, interest in HVO is growing due to the steadily increasing GHG quota and the sub-quota for advanced biofuels.

In addition, by using HVO100, trucking companies can improve their own climate reporting and that of their customers.

7. HVO: Climate savings are exaggerated

The introduction of „HVO100“ in Germany and internationally („renewable diesel“) was accompanied by marketing that was factually incorrect or at least misleading. Time and again, claims were and are made of CO2 savings of “90%”, “up to 90%” or “90% savings potential” compared to fossil diesel.

However, this is demonstrably false. HVO is a mixture of normal hydrogenated vegetable oils (virgin oils), used cooking oil (UCO) and animal fats (AB) in varying compositions, depending on prices and availability.

According to EU (RED II), HVO made from vegetable oils (excluding palm oil) saves 47-51% GHG, HVO-UCO 83-87% and animal fats 77-83%. In addition:

- Land use change effects are set to zero here (dLUC, iLUC).

- Also completely ignored is the effect of palm oil deliveries via China that are almost inevitably misdeclared as UCO .

- Likewise, the effect of CO2 opportunity costs is left out, for example, if animal fats used for biofuels have to be replaced by palm oil in cosmetics.

The numbers demonstrate that a saving of 90% is not possible from a purely mathematical point of view. In the best case (100% true UCO), which will not occur in practice, we are looking at a 87% GHG saving. In practice, however, HVO100 is a mixture of UCO, animal fats and normal vegetable oils. The refineries do not disclose which feedstock components they actually use.

Therefore, a more realistic greenhouse gas saving compared to fossil diesel would be in the range of around 70%. If mislabeled UCO and opportunity effects (displacement effects) are also taken into account, the share could even fall below 50%. That is not a bad result when compared to fossil fuels, but compared to electric mobility, it is not a solution that should be promoted by the state.

Sources:

Ulf Neuling (Agora Verkehrswende): HVO100 – kurz erklärt, December 2024 DOWNLOAD

Cian Delaney (Transport&Environment): Used Cooking Oil: The Certified Unknown, December 2024 DOWNLOAD

Transport&Environment: Pigs do fly!, May 2023. DOWNLOAD

Chris Malins (Cerulogy): The fat of the land: The impact of biofuel demand on the European market for rendered animal fats, May 2023 DOWNLOAD

Horst Fehrenbach, Silvana Bürck (ifeu): CO2-Opportunitätskosten von Biokraftstoffen in Deutschland, 2022 DOWNLOAD

Images:

© Credit Neste Oyj

Schreibe einen Kommentar