1. The Third Quarter 2019

The British-American supermajor delivered as expected, after a string of advance warnings one month ago. Most attention was directed at the profit numbers. Can Big Oil maintain its reputation as ultra-solid cash machine? The first share price reaction on Tuesday was negative. BP shares lost 3.8%.

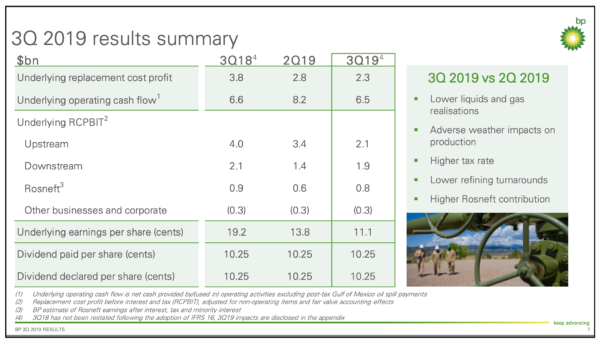

Net profit in Q3 (underlying replacement cost profit) tumbled ~40% from $3.8bn a year ago to $2.3bn. The profit slump would be even higher if the large in-house trading division had not placed a number of successful bets in the oil and gas sector, as the CFO stated. The company does not provide exact numbers but this division is larger than Vitol or Trafigura.

A large impairment charge of $2.6bn, after lower-than-expected revenues from the sale of US gas assets and some other items, meant that BP even had to report an overall net loss of $0.7bn.

A closer look shows that the problem was in the upstream sector. Here RCPBIT (a kind of replacement cost ebitda) halved from $4.0bn a year ago to $2.1bn. This was mainly due to lower oil and gas prices, a major hurricane shutdown and extensive maintenance outages.

Downstream and the contribution from Rosneft (where BP holds a 20% share) remained more or less stable.

2. Not enough earnings: Divestment continues

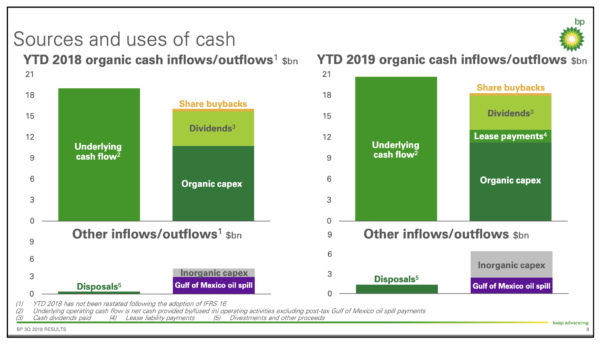

The BP path to financial stability is still slippery. So far in 2019, the firm produced an impressive cash flow of $20.6bn ($6.5bn hereof in Q3). Another $1.4bn was generated by divestments.

So far so good. But the company spends about $2bn more than it earns, namely $23.9bn in the first 9 months of this year.

Hereof organic capex ($11.3bn) is the largest element, plus dividends ($4.0bn), oil spill payments ($2.5bn), inorganic capex ($4.0bn, mostly for BHP assets) and lease liability payments ($1.8bn). And, not to forget, share buybacks for $0.3bn.

So the shale adventure, lots of money to keep shareholders happy, and past sins continue to weigh heavily on BP´s balance sheet.

The strategic conclusion is shrinking, i.e. a large divestment programme. Transactions announced so far this year total $7.2bn. Nevertheless, the financial range for new strategies appears limited.

Net debt stands at $46.5bn, compared with $38.5 billion a year ago. Gearing is 31.7%, compared with 27.1% a year ago. These are pretty high numbers, at least for supermajors.

3. Production in Q3

Upstream production, excluding the Rosneft stake, came in at 2.57 mboe/d oil and gas in Q3. Including Rosneft´s share it was 3.7 mboe/d oil and gas. BP had sold TNK-BP to Rosneft a few years ago, in exchange for a 20% share in Russia´s largest oil producer Rosneft.

BP managed a 4.4% growth in oil and gas production in the third quarter compared to last year. Hurricanes and maintenance could not offset additional volumes from the $10.5bn akquisition of BHP´s shale assets.

Excluding portfolio changes, however, BP’s underlying upstream production, excluding Rosneft, was down 2.5% year-on-year.

4. Low-carbon transition: You need a microscope

BP is lagging behind its more transition-oriented European peers Total, Shell or Equinor. It is more „American“, both in terms of strategy, production focus and culture.

Unsurprisingly, third-quarter numbers, documentation and the conference call did not provide much in terms of transition.

Ethanol-equivalent production was stable against last year at 624 million litres in the first nine months of 2019. BP prefers to present this in litre terms, as the translated 14.500 b/d (or 10.000 b/d in gasoline-equivalent energy terms) do not sound that impressive. The volume equals ~0.6% of BP´s total energy production.

BP´s net wind generation capacity currently stands at 926 MW, lower than the 1431 MW one year ago due to divestments.

Wind power generation fell accordingly to 506 GWh in the third quarter. By the way, this translates into a meagre 3500 b/d oil if we assume that, just for rough comparison purposes, 1 litre oil equals 10 kWh power. Wind represents just ~0.1% of BP´s total energy production.

The solar developer Lightsource BP, in which BP holds 43%, currently manages a portfolio of 2 GW solar facilities. It is one of the largest companies in this sector worldwide and certainly a strong point in BP´s transition portfolio.

Overall, BP did not provide much in terms of strategy. This may be left to the new CEO in February 2020.

5. The other transition: from Dudley to Looney. Leaving the American heritage behind?

CEO Bob Dudley is to retire early next year. He will be replaced by the firm’s upstream boss Bernard Looney (49).

Dudley led the company in a very turbulent period, after he took over from Tony Hayward in the aftermath of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico.

The feared financial collapse of BP did not come, but BP faced clean-up costs and lawsuits that will eventually amount to $75 billion. BP paid $18bn in the last four years alone, and around $65bn so far by 2019. Dudley needed to sell oil and gas assets to pay the bills.

He shrank BP and, in an unexpected turn of events, this was a good starting point after the 2015 collapse of oil prices. Dudley then took BP through a fast growth period. The acquisition of BHP’s US shale oil assets in 2018 for $10.5bn was BP’s biggest deal in the Dudley era.

But he leaves the company without a clear culture or strategy for the transition to low carbon. Critics say that, under Dudley, BP has done too little to reduce carbon emissions and increase investment in renewable energy.

Under his watch, BP has become the „most American“ European oil major: Fossil growth plus lip service to climate change.

The new incoming CEO Bernard Looney spearheaded BP’s efforts in Brazil and West Africa. He also supported the conpany´s digital drive, squeezed costs and delivered projects on time. His upstream division has raised profits from $0.6bn to $14.3bn in just three years, as the FT reported.

BP has made some small-scale investments (and divestments) in wind farms, solar power, biofuels and low-carbon start-ups, but much less so than its peers Shell or Total. As mentioned above, biofuels and wind contribute just a (translated) 0.7% to BP´s total energy production.

The societal pressure for more is mounting though, from the Royal Shakespeare Company and major art institutions cancelling BP’s sponsorships, to activists scaling North Sea oil rigs and shutting down its London headquarters.

Oil may become the new coal sooner than expected, at least in some parts of the world. Investors demand a long-term strategy from the management.

BP’s assets may become “stranded assets” if climate policies gather pace. As FT Lex pointedly wrote, the new CEO may have to write off the oil reserves he himself discovered.

Schreibe einen Kommentar